Cross-posted with ActiveHistory.ca

When I first heard Alvin Dixon’s voice I was driving along Dupont Avenue in Toronto with my partner, Laural, and our three-month-old son, Oscar. Dixon was talking to Rick MacInnes-Rae, who was filling in as the co-host of the CBC Radio show As It Happens. The interview was about Dixon’s experience at the Alberni Indian residential school (AIRS) where he had unwittingly been part of a recently uncovered nutrition experiment conducted by the federal government during the late 1940s and early 1950s.

In addition to describing his memories of the experiment – in impressive and accurate detail – Dixon talked in a jarringly blunt manner about hunger and about the horrors of life in that notorious institution on the west coast of Vancouver Island. “It was totally inadequate food a lot of the time,” Dixon told MacInnes-Rae. “I remember all of us kids having to steal fruit, steal carrots and potatoes so that we could roast potatoes somewhere off site on a fire and eat them – because we were never full when we left the dining room table.”

Dixon had long suspected that something had been done to them at the school. “As early as 20 years ago,” Dixon told MacInnes-Rae, “I heard that there were these experiments from former students who worked in the kitchens.” And when asked what it said to him that his federal government was willing to do this, Dixon responded that it affirmed what he’d always believed: “That the federal government and most Canadians don’t give a shit what happens with us as First Nations people. They’re on our stolen lands, our holy lands and they’re not going to be happy until they have it all. They were trying to eliminate us. So that’s not surprising.”

By the end of the interview I was in tears – something that would happen with increasing frequency over the coming months as I met, corresponded with, and listened to the stories of survivors of these experiments and of Canada’s Indian residential school system more generally. While I’m still not sure what I expected to happen after I published my research on these experiments, I don’t think anything could have prepared me for how profoundly the strength, courage, and anger of survivors like Dixon would change my life and my perspective on what it meant to be an (active) historian.

* * * * * *

The research that first brought these nutrition experiments to the public’s attention was my article, “Administering Colonial Science: Nutrition Research and Human Biomedical Experimentation in Aboriginal Communities and Residential Schools, 1942–1952.” It was published in the May 2013 issue of the scholarly journal Histoire sociale/Social history. The article examined a series of controlled experiments conducted, apparently without the subjects’ informed consent or knowledge, on nearly 1,300 malnourished Aboriginal adults and children in Northern Manitoba and in six Indian residential schools.

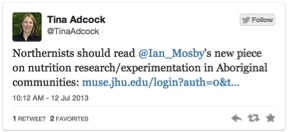

Most Canadian historians aren’t used to the public paying much attention to our research, particularly our articles. But it seems that the recent rise of a vibrant community of historians on social media may have changed things. When my article was first posted online on 12 July 2013, I sent out a brief tweet to my 300 or so Twitter followers letting them know that “My article on nutrition research/human experimentation in Aboriginal communities, residential schools [is] now out” and providing them with a link. A few of my friends and colleagues favourited, retweeted and otherwise congratulated me on my publication. This included Tina Adcock, who sent the following tweet to her more than 600 followers:

At the time, I had little sense that this short, 137 character message would set in motion a series of events that would see my research featured on the front page of newspapers across the country as well as in articles in Nature and the Canadian Medical Association Journal. The fact that it did, though, provides a useful lesson in the power of social media.

Within a few minutes of Tina sending out this tweet, I received an email from Canadian Press (CP) reporter Bob Weber asking if I could “spend about 20 minutes on the phone” with him to discuss my article. From there, things moved rather quickly. I did the interview on Monday, July 15 and the CP story was sent out on the wire at around 1pm on July 16. Within minutes, I was being bombarded with emails, tweets, and phone calls asking for interviews. By 6:30pm I had the surreal experience of hearing my own voice on CBC’s As It Happens as part of the lead story and, by the next morning, the story was on the front page of the Toronto Star, the Vancouver Sun, the Winnipeg Free Press and other newspapers and news websites from coast to coast to coast.

* * * * * *

The next two weeks are something of a blur. I turned down far more interviews than I actually ended up doing, but it still felt like talking to the media had become a full time job. To be quite honest, I was terrified. I was irrationally (or, perhaps, all too realistically) afraid of saying something stupid on national television, of people challenging or discrediting my findings, and of any number of thousands of fears that kept me up most nights for those two weeks.

But, to my surprise, my article began to take on a life of its own, making waves that I couldn’t possibly have anticipated. The Assembly of First Nations unanimously passed an emergency resolution at their annual meeting stating that the experiments “reveal Crown conduct reflecting a pattern of genocide against Indigenous peoples” and calling on the federal government “to develop a system for fair and just restitution for those persons and communities who suffered emotional and physical effects as a result of these experiments and to examine the extent of the residual impacts and intergenerational trauma caused by these experiments.” The Manitoba legislature unanimously passed a resolution calling on the federal government to launch an immediate investigation into these and other nutrition experiments. The minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development, Bernard Valcourt, admitted that the Department was aware of these experiments but stated that they were unwilling to make another apology. And the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) – which had been struggling to have its mandate extended and to be given better access to archival materials – began to use my article as a much-needed political lever to argue for the expansion of its mandate.

Most importantly, this story encouraged the news media to seek out survivors and have them tell their own stories. St. Mary’s Indian residential school and nutrition experiment survivor Steve Skead told the Kenora Daily Miner and News that “We were always starving and some of the boys I used to run with would go out and kill chickadees and we would make a little fire and roast them and that’s how we survived.” Huu-ay-aht First Nation elder and survivor of the nutrition experiments at AIRS, Benson Nookemus, told of similar experiences to the Victoria Times Colonist. “A lot of us were always sick,” he remembered. “We were always hungry. We used to dig up raw potatoes and carrots from the school garden and eat them.” And as Shubenacadie Indian residential school survivor Marie Doyle told the CBC, not only was she always hungry, but she was often given spoiled food. “We’d have a plate of food and if we didn’t like it and threw up, they’d make us eat it anyway. And that was sickening.”

While some survivors told these stories publicly, a large number also began contacting me personally, by email, phone, handwritten letters and through social media. The stories are haunting. The things that these individuals had to live through – the things that were done to them as children – are truly shocking in both their brutality and in their scale. And having attended forums held for survivors of both the Shubenacadie and Alberni Indian residential schools over the past eight months, I can tell you with confidence that these wounds have not healed and that the survivors have many, many questions about whether these were the only experiments that they were subjected to – not just in residential schools but in TB sanatoria, Indian Hospitals, and by local health authorities.

In other words, the confirmation of what had long been known by these survivors – that they were part of some kind of scientific experiment – had unleashed a flood of additional questions yet to be answered. It is, in many ways, a depressing commentary on contemporary Canadian society that such stories were not taken seriously by the government or the media until they were published in an academic journal by a white, male, settler historian. But it is also an important reminder for myself and for other historians that we are often writing from a position of extreme privilege. While academics can use this position to be powerful allies to Indigenous peoples, all too often this privilege is used by settler academics to either speak for Indigenous peoples or to advance their careers and interests at the expense of the communities that they’re claiming to be experts on.

* * * * * *

Perhaps the most beautiful and surprising moment of that first week after the story broke was when hundreds, if not thousands, of Canadians came together at noon on July 25 in parks and public spaces around the country calling on the federal government to #honourtheapology that Prime Minister Harper had made to residential school survivors in 2008 by releasing all relevant documents to the TRC. The event had been organized very, very quickly by Indigenous activists and #IdleNoMore veterans such as Wab Kinew, Niigaan Sinclair, Jodi Stonehouse, Ryan McMahon and others. It started with an online, interactive ‘teach-in’ that I participated in along with Niigaan Sinclair, Ryan McMahon and Anishinaabe elder and residential school survivor Fred Kelly. And, mostly through social media like Twitter and Facebook, rallies were organized in communities ranging from Ottawa, Sudbury, Winnipeg, Saskatoon, Whitehorse, Kamloops and Moose Factory.

As organizer Wab Kinew told reporters in the lead up to the event, the goal was “to provide an outlet for people who are feeling that way to come together, to do something that’s spiritual and commemorative, and provide an emotional outlet for people so they’re not left feeling negative.” And, in many ways, this was exactly what happened at the rally I attended in Toronto. In addition to songs and prayers and a moment of silence for the many thousands of victims of the residential school system, the crowd also heard testimony from survivors as well as from the children and grandchildren of survivors. These were stories of both personal and intergenerational trauma, but also of strength and resilience.

Round dance to #honour the survivors of residential school in #Ottawa. #HonourTheApology pic.twitter.com/sQGDiUpdN8

— Teresa Smith (@proofofsmith) July 25, 2013

But another message was also clear: there can be no reconciliation without truth and many of those at the rally knew that they had only ever been told part of the story of what happened. And so, like at the rallies held across the country, there were powerful, emotional calls for the prime minister to honour his 2008 apology by answering the many questions that still remained about scientific and medical experimentation – not just in residential schools, but in communities, Indian Hospitals, and TB sanatoria, and other institutions.

* * * * * *

Since July, I’ve struggled to figure out why my article garnered the scale of public reaction that it did. Obviously, the story it tells is shocking, but parts of these experiments had actually come to light more than a decade earlier following an article in the Anglican Journal by journalist David Napier. Yet, aside from a few short articles, including one in the Vancouver Sun, the story didn’t seem to garner much in the way of a response from the public, the media, or the government. The same was true of revelations by historian Maureen Lux that the National Research Council used Indigenous children as experimental research subjects in southern Saskatchewan for experimental trials of BCG vaccines for tuberculosis. While these experiments were of a similarly ethically dubious nature, Lux’s revelations garnered virtually no public response from the media. And, most importantly, survivors of residential schools had been baring their souls and their stories of profound physical, spiritual, emotional, and psychological abuse in residential schools to the Canadian public by the thousands as part of the TRC events that had been happening across the country. Many of these stories described abuse that was far more shocking and terrifying than what happened as part of the government’s nutrition experiments, yet the TRC’s work had seen only scattered and sporadic news coverage.

As I’ve already suggested, it’s likely that my status as a white, male, settler historian played an important role in the scale of public response to my article. The fact that survivors have been saying such things for years without much in the way of any kind of media attention only highlights the role played by my undeniably privileged status. But another important factor was also probably the timing of my article’s publication. The TRC’s struggle to get the government to cooperate with its efforts to collect all of the relevant documents related to residential schools and the need for the government to extend its mandate due to the large number of documents that still needed to be collected and analyzed had been making headlines. The Assembly of First Nations was also holding its annual meeting when the story broke and their emergency resolution calling for answers helped add fuel to the media fire.

Another part of the public response had to do with social media. The story had initially been discovered by journalists because of the presence of a community of historians on Twitter. But the rapid spread of the story can also be attributed to a new generation of young, smart, articulate, and creative Indigenous activists on social media. Many of these were the same activists that had made #IdleNoMore into one of Canada’s first social media driven political movements. And the network that helped spread the #IdleNoMore message ensured that news reports about these experiments – and even my article itself – were shared thousands of times on Facebook, Twitter, blogs, Reddit and other online forums. The efforts of fellow historian Jim Clifford, myself and others to have the article made open access helped with this, although the article had already been (and continues to be) shared extensively through websites, Dropbox accounts, and via email.

In other words, while the mainstream media’s coverage had initially got the story out there in the first place, social media and the efforts of Indigenous activists kept it alive for much longer than it otherwise would have been.

But I think the most important factor defining the sheer scale of the response to my article is that it seems to have confirmed, for the media at least, what had long been considered to be common knowledge in Indigenous communities around the country. This meant that when journalists came calling with questions about the nutrition experiments, they began to hear other stories as well. In fact, when CBC journalist Jody Porter began digging, she managed to uncover another experiment on the treatment of ear infections at the Cecelia Jeffrey residential school that may have led to serious health complications for the children involved.

It’s also possible that the revelations of the sheer scale of these experiments confronted many Canadians with their own false assumptions about residential schools, in particular. Most Canadians still don’t know anything about the residential school system at all, but many of those who do still seem to believe that they were largely benevolent institutions and that the stories of abuse have been exaggerated. But these revelations highlighted what survivors of residential schools and historians have long known: that the residential school system not only tore children away from their families, their culture, their language, and their communities but also that they deprived children of many of the basic necessities of life like food, clothing and proper medical care.

Many Canadians (and many journalists, it seems) were therefore shocked to learn that – not only did the federal government know that hunger and malnutrition was systemic at these schools – but that top government officials nonetheless chose to use this as an opportunity for scientific research rather than as a problem in need of an immediate solution. In other words, it was not just a few “bad apples” taking advantage at their position of authority at these schools in order to physically and sexually abuse students: the entire system, many were finally beginning to realize, was at its very core abusive and inhumane.

* * * * * *

I still don’t know what to make of my experience as an accidental public historian. To be quite honest, I’m still a little bit in shock that it happened at all. My work has reached places that I never could have imagined and I’ve met so many amazing, inspiring people along the way. Talking with the media is sometimes an discouraging or even terrifying experience – especially when they get the facts wrong or clearly didn’t read your article before writing or talking about it – but it has also opened up many doors.

One thing that has become clear to me over the past few months is that, when our academic work finally gets published, it ceases to be ours. Its meaning is ultimately determined by our readers who give it life, give it meaning, and bring their own knowledge and experiences to it in ways that we could never have expected. In the case of my article, in particular, the media tried to make it into a certain kind of a story: a story about a distant past, one that we have moved beyond and left behind. The survivors, though, have made it into something else. It has become a confirmation of stories that they have long known to be true but that have been, for too long, dismissed or simply ignored by Canadians.

But it has also opened up far more questions than it has answered. I know this is true, in large part, because I’ve had the profound privilege and honour to meet with survivors of these experiments at forums organized by the Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia and by the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council in British Columbia. These survivors are easily some of the strongest, most inspiring people I’ll ever meet and their stories will stay with me forever. But they also had many, many questions about what happened to them in residential schools, Indian Hospitals and TB sanatoria that have gone unanswered for far too long. The same is true for the many individuals who have contacted me by mail, phone, email, Twitter and in person with haunting stories of abuse and questions about whether or not they were part of some kind of scientific experiment. While there is hope that the TRC will be able to finally provide answers to some of these questions, the government’s unwillingness to cooperate with the commission has genuinely brought into question this government’s commitment to either truth or reconciliation.

We’ll have to wait to see what the future will bring – and whether the survivors will really be provided with the truth about what happened to them in residential schools. But I know that my work from this point on will be dedicated to helping to answer as many of these questions as I possibly can.