Cross-posted with ActiveHistory.ca

As a historian of food and nutrition, I’ve amassed a substantial collection of cookbooks, old and new, over the years. But one cookbook I often find myself coming back to amidst the hundred plus dusty volumes cluttering my office is a 1930 edition of the Good Housekeeping Institute’s Meals Tested, Tasted and Approved: Favorite Recipes and Menus From Our Kitchens to Yours. I purchased it for $12 from a Toronto vintage shop and consider it one of my favourite purchases to date.

As a historian of food and nutrition, I’ve amassed a substantial collection of cookbooks, old and new, over the years. But one cookbook I often find myself coming back to amidst the hundred plus dusty volumes cluttering my office is a 1930 edition of the Good Housekeeping Institute’s Meals Tested, Tasted and Approved: Favorite Recipes and Menus From Our Kitchens to Yours. I purchased it for $12 from a Toronto vintage shop and consider it one of my favourite purchases to date.

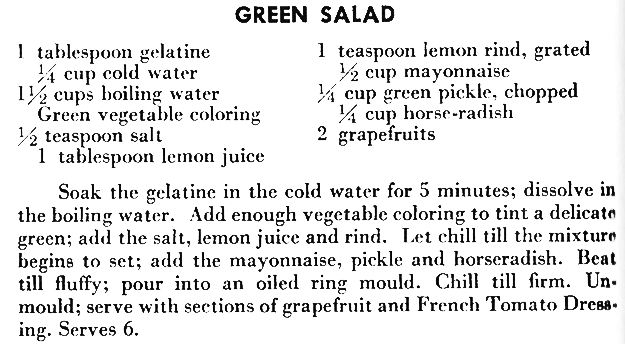

On the surface, at least, the cookbook seems unremarkable. Good Housekeeping cookbooks from the period are common enough, and like many others in my collection it’s well worn and smells vaguely of mildew and decades-old flour. Its spine is broken and held together with clear tape. Its pages are stuffed with dozens of handwritten recipes on cards as well as a number of others cut from newspapers and magazines. These include a fading recipe for Dandelion Wine written in pencil on a piece of scrap paper and a Campbell’s Soup can label with a recipe for Oven Glazed Chicken. In other words, it’s a cookbook like hundreds of others that could be found in kitchen cupboards in households across the country, and my personal collection includes its own fair share of similarly well-worn, well-loved volumes.

But what makes this particular cookbook remarkable – to me at least – is the inscription in the front cover left by its original owner, Jean Stephenson.[1]

My first cookbook, I was 18 yrs. old, living on my own employed, as an artist. This book was sent to subscribers of the Good Housekeeping Magazine that was full of information for the young, starting life together in the 1930 yrs.

Jean Stephenson

Still very good in 1997.

Then, with a different pen, likely written later on:

Engaged to Ben at 19

Married at . . . . 21 in 1932.

We had 57½ good years. Together…

And, finally, with another pen altogether:

Ben [passed] away

No illness at 84½ yrs.

In 1989.

I’ve always found this inscription very sweet, more than little sad, but also a powerful example of how even the most utilitarian cookbooks can become something more than just a simple directory of recipes. During my doctoral research, I became well acquainted with reading the multiple narratives embedded in cookbooks of all kinds. Of course, most of my sources were generally not as personal as Jean’s. But I could still read community cookbooks, for instance, in order to examine how they were often used to articulate and even define the boundaries of inclusion and exclusion within the church group, voluntary association, political party, or city that they were claiming to represent. I also quickly became well attuned to the ways in which mass-market cookbooks published by celebrity home economists or popular magazines did more than simply provide interesting recipes, but also tended to include extended meditations on women’s appropriate behavior in and outside the home through chapters on etiquette, table manners, and economical and scientific shopping practices.

But, as Jean’s inscriptions suggest quite forcefully, cookbooks tell us something much more personal about their readers, as well. The problem is, we often only come about this information by inference – particularly when we know nothing about the original owner. Still, many cookbooks do offer at least a few tantalizing clues who owned them and how they were used.

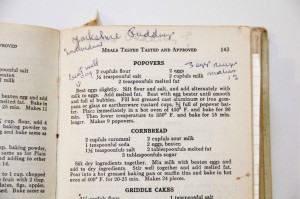

For instance, the pages showing the most use in Jean’s cookbook – i.e. the stained, dog-eared, discolored, and heavily annotated pages – are primarily in the baking section, particularly those with recipes for cookies, breads, and cakes. The recipe for Popovers, for instance, shows almost all of the above-mentioned signs of use, including annotations. The penciled in question “Yorkshire Pudding?” above the recipe appears to have been answered later on with the more confident words “Yorkshire Pudding” written over-top in blue ink and with a number of additions like “beat very well” written in pen over the original instruction to “beat eggs slightly.”

For instance, the pages showing the most use in Jean’s cookbook – i.e. the stained, dog-eared, discolored, and heavily annotated pages – are primarily in the baking section, particularly those with recipes for cookies, breads, and cakes. The recipe for Popovers, for instance, shows almost all of the above-mentioned signs of use, including annotations. The penciled in question “Yorkshire Pudding?” above the recipe appears to have been answered later on with the more confident words “Yorkshire Pudding” written over-top in blue ink and with a number of additions like “beat very well” written in pen over the original instruction to “beat eggs slightly.”

There’s other evidence that Jean adapted the recipes to her tastes over time and was willing to experiment with recipes that didn’t seem to work. Among the most stained pages is one with a recipe for Fruit Cake and, tucked in among the other recipes and cooking ephemera, is a day-planner page filled with the results of Jean’s research on how to improve the recipe, with handwritten notes on the variations of the recipe she found in the American Woman’s Cook Book (1947) and Ana Lee Scott’s Cooking Secrets (1934). The fact that such addendums were included along with a number of other “improvements” on recipes already in the cookbook, either written on paper or cut out from magazines and food packaging, suggests that Jean was always looking for better recipes, particularly for holiday baked goods.

But what I like best about Jean’s cookbook is how much it meant to her, beyond being simply a handy source of tested recipes. Her short biography written in the front pages makes this clear. Not only did she connect some of the key moments in her life to this particular book, but the fact that she added to her inscription on three separate occasions suggests that reading the cookbook acted as a powerful trigger for these memories of her youth, of her long and happy marriage, and of her husband’s death. I never knew Jean, so the actual content of these memories are lost, but I imagine that they flooded back to her every time she picked up the book from her shelf – just like my own do when I look through the cookbook that I helped my mother put together using recipes from my childhood.

This is what, I think, makes the inscription carry a note of sadness, separate from the death of Ben. This book clearly meant a great deal to Jean yet, after her death in 2009, it was not seen by those close to her as something worth holding on to. And this, I fear, is probably the fate of many such cookbooks. Much of their meaning is attached to their individual owners but, when this connection is lost, the memories associated with them are probably gone forever, as well. Jean left a few hints about her life in the front pages of the book but, as I know from experience, this is quite rare. Few cookbooks contain even the name of their owner, let alone information such as when they came into possession of it or how long they’ve been using it.

One reason why I think Jean’s cookbook may have been given away is related to the lack of value we, as a society, assign to cookbooks and women’s culinary literature more generally. Libraries and archives – the official repositories for Canada’s print heritage – typically afford little respect to cookbooks. Leading culinary historian Elizabeth Driver, for instance, found in the course of her research for Culinary Landmarks: A Bibliography of Canadian Cookbooks, 1825-1949 (2008) that more than 1000 of the 2275 cookbooks she was able to identify from the period were not in libraries or archives at all but, instead, could only be found in private or personal collections.[2]

While some libraries and archives are working hard to remedy this situation, I would argue that our longstanding failure until now to protect Canada’s culinary heritage has always been a reflection of the lack of respect afforded to women’s work in the kitchen, more generally. Cooking has always been a key component of a broader set of gendered expectations placed upon women as wives, mothers, and daughters. As Diane Tye and others argue, the sheer weight of these expectations meant that, during most of the twentieth century, cooking became a form of women’s seemingly unending “invisible labour” – the constant, unpaid work that sustains the household and the family but usually receives little in the way of comment or acknowledgement, particularly when it is being done well.[3]

To a certain extent, I think that this discounting of the importance of women’s labour in the kitchen is one of the reasons why food history is often perceived as being less ‘serious’ than other areas of inquiry. I can’t tell you how many times another historian or colleague has told me that my research sounds ‘fun’ – at times seeming to imply that it’s somehow easier and less challenging than other areas of scholarly inquiry – even though most women during the period I study would likely associate cooking with work more than pleasure.

I don’t know how Jean felt about cooking but, after a bit of online sleuthing, I can tell you that it was a big part of her life. After having children, she gave up her career as an artist and, in all of the obituaries and tributes I read, there are references to her warmth, hospitality, and how she was well known for welcoming with open arms the guests from around the world that – because of her husband’s particular line of work –regularly passed through her home. I feel lucky to have found this cookbook and, through it, learn about more about her fascinating life and times.

Perhaps I’ll leave you with this thought: taking care of our cookbooks – within our families and in our archives – is an important component of celebrating and affording respect to the lives and work of ordinary women. It is therefore very much a feminist project and it’s one that social historians, in particular, should be spearheading. If you have any interest in sharing your cookbooks or stories, I would love to hear from you. Leave a comment or send me an email at imosby (at) uoguelph.ca.

[1]Both Jean and Ben Stephenson are pseudonyms.

[2] Elizabeth Driver, Culinary Landmarks: A Bibliography of Canadian Cookbooks, 1825-1949 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008), p. xx.

[3] Diane Tye, Baking As Biography: A Life Story in Recipes (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010) 96. My favourite work on women’s household labour in the Canadian context is Meg Luxton’s More Than a Labour of Love: Three Generations of Women’s Work in the Home (Toronto: The Women’s Press, 1980).